Jim Senior:

"Are you talking about principal rafters or common rafters. In the latter case you don't want some rafters touching posts because shrinkage of the plates will mean that the rafters on the posts finish up out-of-plane when the timbers dry."

I am speaking of both primary as well as common rafters. The effect of shrinkage is an interesting one, which could possibly explain why this won't work, since I suppose the plate would 'round out' any uneven shrinkage post-to-post somewhat, and I would not have the same benefit. If all rafters tied to posts (I have a closely-spaced layout of about 4ft centers), would there likely be less cause for concern?

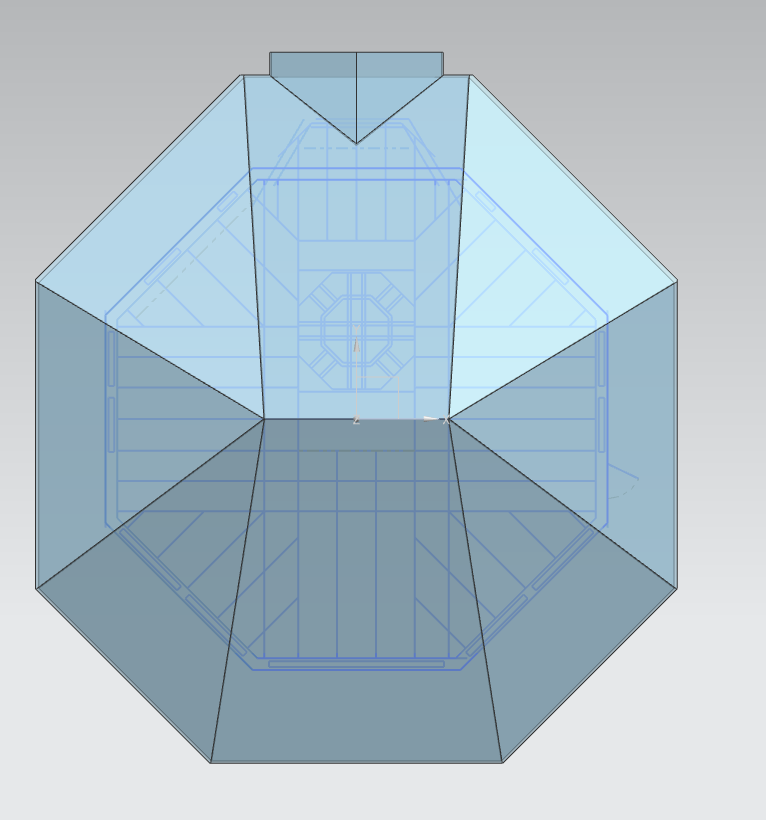

This is my 'first pass' attempt at the roof profiles (overlaid on the interior ceiling joist layout); I fully expect the trapezoidal facets to become rectangular for simplicity, or otherwise tweaked for the ridgelines to line up with desirable structure. The goal here is a more 'typical' hipped roof appearance on an octagonal frame. It seems difficult to get a decent looking roof on an octagonal floor plan that isn't conical or domed, and my attempt is to put up a ridge beam so the roof line is flat rather than pointed from the front approach.

"In French carpentry you'd place a "gousset" and "Coyer" to receive the rafter."

The gousset (any relation to 'gusset?') or dragon beam idea does seem interesting, since I will have a post off to either side of the corner, conveniently located to directly support such a feature, even if the rafter is seated right over the corner where there is no post. Since the angle is 135deg at the corner, it may be difficult to accomplish without making the gousset length or its joint volumes very large, but it would definitely help reinforce the wall angle/shear strength of the structure, which has been one area I've been a bit unsure of (my plan had been to rely on shear stiffness in the floor/ceiling assemblies, but this is more direct)

"In an octagonal structure I see even less of an advantage in removing the plate. Your rafters are going to all meet in the center so you can't raise the post and rafter at the same time. Better to have the posts all raised and solidly assembled to on another to provide a base on which to place the rafters."

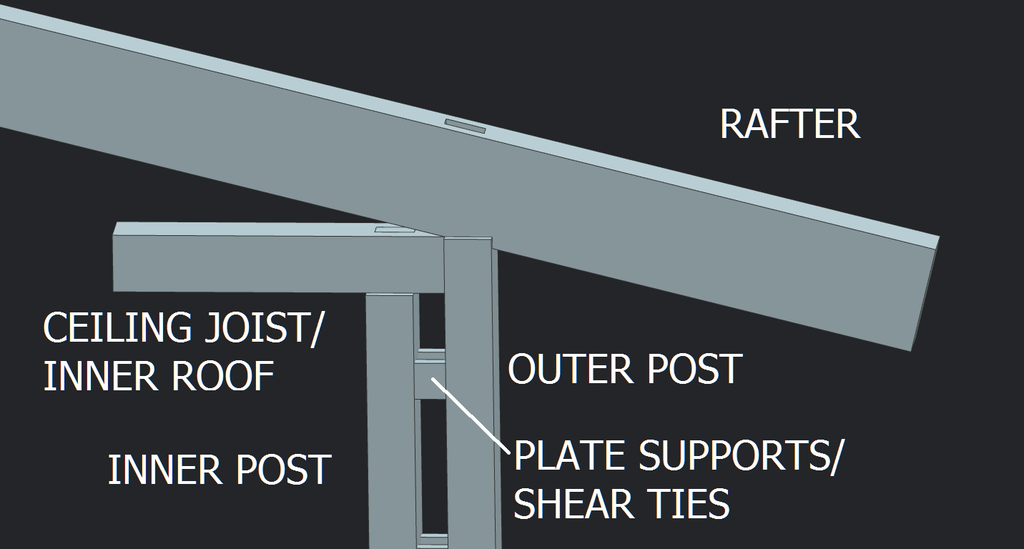

I was thinking more along the lines of moving the plate from atop the posts (either higher into the rafter assembly, or lower into the wall assembly), than of removing it altogether, which as you say, would make raising more obnoxious for sure. My construction scheme broadly relies on there being eight separate wall assemblies that are essentially prefabbed (sort of like bents, only going tangentially rather than linearly, and tied directly to each other at the corners), so it makes infinitely more sense for there to be some sort of horizontal member at the upper end of the wall. In that case, I'd be looking primarily at laying a plate/horizontal tie beam slightly below the joints for ceiling joists & rafters, probably at the upper window frame line (possibly laying across the top of the short shear ties in the diagram below)

I show the joints as through mortises for some level of clarity, but they obviously don't actually need to be so, beyond construction simplicity. The wall plate would sit on those 'shear tie' short pieces joining the posts, notched so as to carry/transfer stabilizing side forces to the vertical members. Since the plate is no longer directly carrying weight from above, my assumption (pending analysis) is it need not rest directly on the posts.

"Caveat: I'm not an engineer, and living in France, the codes that I know are the European ones."

Caveat: I am an engineer, but I know little of any code (for now)

--thanks for weighing in, Jon

Timbeal:

"Another possible issue to consider when extending rafters outside the envelope is insulation and the trim detail, to be exact the fascia board and its width along with these exposed or not exposed tails can accumulate in an extra thick over hang, sometime its fine and other times its not so fine."

I wrestled with the eaves/fascia issue also, since my roof design necessarily calls for three different pitches of overhang (an obvious no-no in general, as far as easy trim construction). It's a total cop-out, but my 'solution' was to attach fascia boards at a fixed height (they would be parallelogram or trapezoid shaped, depending on which roof facet). This at least keeps the wasps out of the eaves for the most part, and hides the varied roof-over-plate height. It would only extend a short ways from the wall, most likely no further than a couple feet. Definitely a function over form design consequence to be sure, though, and one I see mentioned frequently on even seemingly simple structures.

I think the insulation issue is sufficiently addressed by the double-wall-double-frame layout I'm pursuing (both about 1ft thick at the corner). It's basically a wall-truss, only beefed up enough on the inside to carry the ceiling and floor joists (the ceiling joists may or may not tie to the rafters, depending on their structural needs). To be honest, I'm more worried about rot/repair potential of the cantilevered rafters over the long run; seems like it could potentially be a nightmare to replace the ends once they give up the ghost. I simply don't know what or how much consideration repair service needs to be prioritized.

"So terminate the rafter tails at the wall and let the sheathing or insulation system create the over hangs."

My overhang is rather generous to provide a canopy for a patio/walkway, about 8ft at the longest; there will definitely be some sort of rafter-ery required for that, be it spliced to the roof rafters or a thinner extension supported by orthogonal bracing. I'm trying to avoid knee braces for head-room reasons, and exterior posts since I fear they'd rot without roof coverage. I had assumed that utilizing the existing rafter lines would be the most efficient route, but it also appears that to do so requires chopping away much of their cross sectional area for the wall joinery. My pitch is around 14degrees, so in my case the cross section removal isn't quite so terrible, but my quest for a possible workaround remains.

Jim Rogers:

"What Jon is talking about is called a Dragon and Cross for the hip rafter to sit on."

Thanks for the nomenclature; I do like how this system basically moves the joint locations away from the same point on the frame, while at the same time providing planar stiffness in another direction. My corners may not be sharp enough at the exterior to make use of it, but I'll bet it'd be perfect for connecting joists at the inevitable 45deg angles inherent to an octagon.

TCB